Insulators have been around longer than

most people realize. The first rudimentary telegraph line was

built between Paris and Lille, France in 1793. The need for insulators

to insulate the wire from grounding out soon became apparent.

There were a number of early experimental lines in Europe and

the United States before Samuel F. B. Morse finally developed

a fully functional and commercial system using his particular

code. He built his first commercial line between Baltimore and

Washington, D.C. in 1844.

Insulators were first used extensively in

the mid-1840s with the invention of the telegraph. They were necessary

to prevent the electrical current passing through the wire from

grounding out on the pole and making the line unusable. The first

insulators were a beeswax soaked rag wrapped around the wire.

They worked well in the dry laboratory but soon broke down when

exposed to the weather. The next concept was a glass knob, which

looked much like a bureau knob one might still find on antique

furniture today, mounted on a wood or metal pin. From this evolved

the pin style insulator, which had no threading inside the pinhole.

It was cemented to the pin by driving it down on the pin with

a mallet on an asphalted rag. This was not a perfect answer because

the weather worked on the rag and eventually the insulator would

work loose and pop off the pin allowing the wire to contact a

grounding surface. Inevitably, however, as telegraph lines traced

the westward expansion of railroad lines across the states, glass

manufacturers began to create many new designs in an effort to

secure a niche in the rapidly growing insulator market.

Thus, by the advent of the Civil War in

1860, original insulator models could be found in both porcelain

and glass. While glass was more common from the beginning for

telegraph and telephone line insulation, porcelain would later

gain a firm foothold as the preferred material for insulating

high voltage power lines. Over time, glass manufacturers would

produce hundreds of designs; millions of insulators were made

of glass and porcelain, then later of rubber, plastic and other

composite materials.

While even the earliest mass-produced insulators

were constructed with the still familiar wire grooves through

which the line wires run, insulators were at first made with non-threaded

pinholes. The insulator was simply stuck on the top of a wooden

peg or branch. It wasn’t until July 25, 1865 that a carpenter,

Louis A. Cauvet, invented and patented the threaded pinhole design

we still find in insulators lying along old railroad tracks throughout

the country. It was a method for threading the inside pinhole

of the insulator, which then could be screwed down on a threaded

wood or metal pin.

Though Cauvet’s concept was at first

ridiculed as too inefficient as it made installing insulators

more time consuming, his design succeeded in ensuring the insulators

wouldn’t fall from their lofty perches when battered by heavy

winds and storms—a significant problem with non-threaded

designs. Ultimately the Brookfield Company purchased Cauvet’s

patent and the design turned out to be so successful it remains

basically unchanged even on modern porcelain insulators.

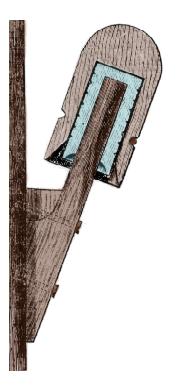

Cross-sectional Drawing

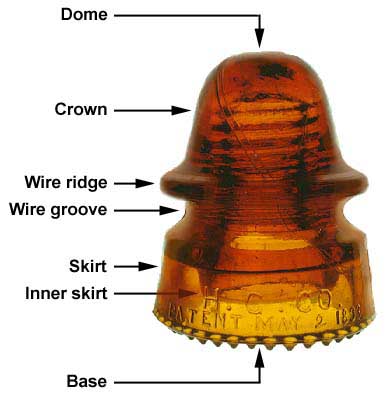

Parts of a typical insulator

This is an example of how insulators are attached

Cross-sectional Drawing

Parts of a typical insulator

This is an example of how insulators are attached

The cross section shows the wood covering

enshrouding a Wade glass insulator, which is attached to the wooden

pin on the bracket.

This cut was taken from the book "Modern

Practice of the Electric Telegraph" by Frank L. Pope

(1869) which depicted the insulator styles commonly used in that

period and especially during the Civil War.

Insulator on telegraph pole

Insulator on telegraph pole

The "Confederate Egg" telegraph

line insulator was so called because it resembled an egg. The

wire groove is very noticeable in the center. The South had the

capacity to reproduce enough insulators to cover normal wear and

tear. It didn’t have the ability to mass-produce the number

needed after the war started due to deliberate damage inflicted

by opposing troops. So the ones you see on display represent very

crude manufacture of insulators for telegraph lines for the Confederacy.

The above example was found in Mobile Bay,

Alabama. They were very rare until a large cache was found in

remains of a Confederate Storage Depot in Richmond, Va. in 1990.

Richmond was the capitol of the Confederate States. Rebels torched

the depot during Yankee advances in April 1865. There are many

colors including deep greens, emerald greens, and cobalt. All

glass "eggs" of these types possibly were made at Richmond

Glass Works, known to have made telegraph insulators of some sort

during the war.

We at the Drum are proud to have on display

the above Confederate "Eggs." Sherman’s Yankees

burned the melted one as they destroyed the telegraph system when

they marched to the sea.

(We have no information of when

or where they were found)

There is a whole subculture dedicated to collecting insulators,

especially in the U.S. and also the world. Much more information

can be found on the web and at public libraries.

Bibliography:

"Early & Unused Telegraph Insulator," by Mike Guthrie

"History of Insulators," by Mike Scott of "Glass House Productions"

"Insulators thru the Ages,"

by Jim Woods: and photos from the

web site of Bill Meier called,"Glass Insulators."

Floyd Farrar, Drum Volunteer,

June 2001.